How GWS Started

George Guthridge (“Dr. G.,” as his students used to affectionately call him) was a D student in high school.

But he knew how to write.

Using that ability, he graduated second in the university and became a full-time professor the day before his 24th birthday. He was the youngest professor in the English Department by 18 years.

Since he had majored in writing, the department faculty mandated that he review the composition textbooks publishers had sent the college in the hope of adopting them.

There were over 300!

♦

By happenstance, an event happened that week that changed his life.

The college required every composition student to write a research paper at least 10 pages long.

Dr. G. had 118 students. All week, a line formed outside his office as students came to tell him their topics.

The last student arrived at 7 pm on Friday.

“I’m going to write on the French Revolution,” she told him.

“What about the French Revolution?” he asked.

“The French Revolution,” she said.

“What about it?” he politely asked.

“I’m going to tell the story of the entire French Revolution,” she said.

“In ten pages?” he asked incredulously.

“Yes.”

“Ten pages is twenty-five minutes of talking,” he said. “So you’re telling me you can cover the entire French Revolution, one of the most important events in the history of the world, in twenty-five minutes?”

“Yes,” she insisted.

“That’s impossible,” he said.

“Not for me it isn’t,” she said. “I’m a journalism major.”

♦

No matter how much Dr. G. tried to have her narrow her topic, she refused to budge.

Finally, he said, “Look, I’m not trying to be cruel. But if you attempt to cover the entire French Revolution in ten pages, the paper will be an F.”

She stomped out of his office.

The next day, a Saturday, Dr. G. began the task of assessing 300+ composition books that lined the shelves of an otherwise empty room.

His discovery so stunned him that he ended up sitting slump-shouldered on the floor.

Not one of the composition books showed, step-by-step, how to narrow a topic.

Not one.

Even though, as a writer, Dr. G. knew that 80 percent of effective writing involves choosing an excellent topic.

Some books did not cover subject selection at all. Some gave examples of subjects but without showing students how to choose one. Many of the examples were poor.

The “experts,” most with doctorates, did not know how to teach students to limit a subject.

♦

Dr. G. eventually persuaded the journalism major to narrow her focus. After all, one of her classmates was writing about “The Weight of English Cannonballs as One Reason for the Defeat of the Spanish Armada.”

All that summer, though, he stewed about subject selection.

English teachers and professors tell students to limit your topic. Focus. Narrow your idea.

But they don’t tell them how.

Moreover, what students think is a narrow or focused or limited topic is not what educators know it to be.

The result? Confusion and, often, animosity.

That summer, Dr. G. set about on a quest that would consume him for 46 years. He wanted to design a system that would take the mystery out of learning to write so students could do what he did naturally. He wanted every step in the process to be concrete. He later would learn that what he was attempting has never been done before.

The next fall, a student in her thirties took his research-paper course. A recent widow, she wanted something to fill her time – part of the grieving process.

Her proposed topic? The Effect of Midwestern Storms on the Migration of Canadian Geese.

An idea hit Dr. G.

Maybe, he thought, the problem with subject selection wasn’t so much in the teaching, or lack of it. Maybe the problem lay in the words teachers used to describe the process.

What if what we call a narrow or focused or limited topic is at fault.

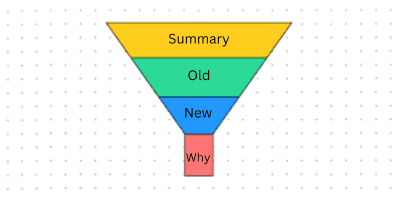

What if, he asked himself, we look at subject selection in terms of variables:

Old Information – What the intended reader probably knows a lot about or does not care about.

New Information – What the intended reader probably does not know much about and is probably interested in.

Why – Why the New Information is true or important.

Students could add a summary (which goes at the beginning of documents, not at the end) and have the following organization. It looks like a funnel:

♦

The results were stunning. Many students in developmental English had articles accepted by nationally circulated magazines. And his students were so successful at writing research papers that he was tenured the day before his 30th birthday.

Dr. G. later met George R.R. Martin, now of Game of Thornes fame. George RR got Dr. G. interested in writing science fiction, fantasy, and horror fiction. Dr. G. left teaching in order to write full-time.

Dr. G. was successful at writing fiction. He supported his family of four writing short stories for national magazines.

But he missed the classroom.

After he saw an ad for teaching on St. Lawrence in the Bering Sea, he and his family moved to the Siberian-Yupik village of Gambell. They could see Siberia from their front door. The village had no roads. No running water except in the school. Windchills that often plummeted to -140° Fahrenheit.

After seeing some of the students’ potential, he told the high-school’s five other teachers that he thought the Gambell students could win Future Problem Solving’s state championship in five years.

Three of the teachers laughed in his face.

After all, Future Problem Solving (FPS) was the nation’s most difficult academic competition. And the Gambell students had no computers, no books, and low reading and writing scores. They spoke English as a second language and had little world knowledge.

Dr. G. was wrong about the prediction.

They did not win the state championship in five years.

They won the national championship in two years. On both the junior-high and high-school levels.

♦

He has been asked many times how the students accomplished such a feat, especially against such overwhelming odds.

The students worked very hard, of course. But they had two writing techniques. Ones that became the basis of GWS – The Guthridge Writing Method.

The Enthymeme*

Dr. G. first encountered this in research he was doing as an undergraduate student. It is a teaching concept that the Ancient Greeks used to train their young citizens to be effective communicators. However, the notes of the great philosopher, Aristotle, about its exact implementation were lost for many years and, when found, were misinterpreted. Aristotle said that if people understand how to use it, they will know almost everything they should know about communications. And, if they understand the enthymeme’s relationship to example, they will know everything they need to know.

Indigenous Learning

Toward the end of his second year on St. Lawrence Island, Dr. G. was watching village elders build a skinboat. The techniques, which were very sophisticated, were thousands of years old. He realized that, by using Alaska Native learning methods, he could teach students very complex ideas right away rather than starting with simple ones. He had stumbled upon the same method that the genius music teacher, Japan’s Shinichi Suzuki, created for teaching Japanese children to play the violin. Regardless of ability, they begin with Mozart. The Future Problem-Solving Program’s subject area for the national finals was on genetic engineering. Only one of the ten students involved in FPS had even heard of the subject. Forty-four days later, the national evaluators had to phone a geneticist. They could not understand the Gambell students’ answers. The students had mastered what they needed to know about genetic engineering because Dr. G. had applied Alaska Native learning.

Today, over 2500 of Dr. G.’s students from rural Alaska – 94 percent of whom are Alaska Native – have graduated from college. They use GWS, which combines the enthymeme and indigenous cogitation.

_______________

*For ease of learning, Dr. G. initially calls this the What/Why Statement and later the hyperthesis, due to its close relationship to Aristotle’s concept of the hypothesis